This is a repost of an article we wrote for Sarvodaya after the Tsunami of 2005. We are considering a return to Sri Lanka next fall, which prompted me to dig out this piece. We miss Sarvodaya and our friends there and hope the civil war stabilizes so that we feel comfortable making the trip.

Someone asked me today why I write this stuff. I feel compelled.

Our Mission

We were making our first trip to Sri Lanka in 3 and 6 years, respectively, to see our friends at Sarvodaya and to find a tsunami impacted village that needed a preschool—the heart of the Sarvodaya village development process. The International Student Association at the Louisiana State University (where Rich is a professor and I am an adjunct) under the student leadership of Francisco Aguilar a former volunteer for Sarvodaya, with the support of Virginia Grenier at the LSU International Hospitality Foundation had raised over $5,800 through a series of concerts to build a preschool; these monies were generously matched by our friend Rick Brooks at SHARE in Madison, Wisconsin for an additional $3,500. Thus, we had enough money, we were told, for possibly two preschools, depending on whether we had to construct them outright or whether they simply needed repair and reconstruction.

Before we embarked on our trip, Sarvodaya Headquarters had determined that the Matara District was the tsunami-impacted area that needed our help. We learned that what would have been a relatively simple task before the tsunami—determining which village in which to build a preschool—was a multifaceted and complex task in post-tsunami Sri Lanka.

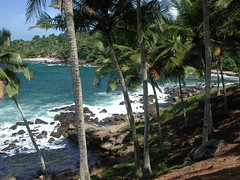

Traveling on Galle Road

We left for Matara under the care of Vinya’s driver, “Mutu” to see where the preschool was to be built, or if a village had not been  identified, to choose the most appropriate village in which to build. Traveling on the coastal road (Galle Road) the devastation was still apparent, the majority of which appeared to be around the City of Galle itself. Houses and other structures were totally ripped from their foundations, with partial cement walls standing to mark the place where the structures had been. In other instances, nothing was left except rubble or garbage strewn on the ground.

identified, to choose the most appropriate village in which to build. Traveling on the coastal road (Galle Road) the devastation was still apparent, the majority of which appeared to be around the City of Galle itself. Houses and other structures were totally ripped from their foundations, with partial cement walls standing to mark the place where the structures had been. In other instances, nothing was left except rubble or garbage strewn on the ground.

‘Temporary housing’ in the form of tent cities were scattered amidst the broken cement, each of a different color and with various emblems depending on the donor. They looked hot. Sometimes mixed in with the tents were ‘semi-temporary housing’ units about half the size of a small U.S. bedroom, of rough, crooked lumber without window coverings, running water or plumbing. They looked like my children constructed them and didn’t look like they could house a family for any length of time. From time to time, Mutu would say “tsunami” and sweep his hand dramatically over the terrain to indicate where a particularly bad stretch of devastation had occurred.

Brightly colored boats were strewn in various broken states on the sand and land, with remnants of nets draping what was left of the boat or bunched in a pile on the sand. The boats looked strangely beautiful even though they were in pieces. The devastation was oddly uneven.We would drive past rubble the size of pebbles and shortly thereafter we would see a stretch housing along the beach that appeared untouched. Individuals were busy mending walls of structures along the road with whatever materials they could find. Toward the District of Matara, however, the tsunami devastation appeared to be less severe, and that there was a greater organized repair effort underway. Mr. Senerath told and retold stories of Buddha statues, shrines and stupas that were untouched by the tsunami, some right next to great piles of wreckage, and about dogs that alerted their owners and retreated inland before the tsunami struck.

Individuals were busy mending walls of structures along the road with whatever materials they could find. Toward the District of Matara, however, the tsunami devastation appeared to be less severe, and that there was a greater organized repair effort underway. Mr. Senerath told and retold stories of Buddha statues, shrines and stupas that were untouched by the tsunami, some right next to great piles of wreckage, and about dogs that alerted their owners and retreated inland before the tsunami struck.

We stopped abruptly beside a USAID tent city, where Subasena from Sarvodaya Headquarters was standing waiting for us. He informed us that our hotel, located high on a hill was spared (the Matara District Center does not have housing available and many hotels along the beach were destroyed) and that “H.M. Nelson,” the District Coordinator was waiting for us at the District Center.

The Matara District Center

We came to the Matara District Center and Nelson and Ninsanke (from the legal aid unit, who assists with the effort to reproduce lost documentation such as birth certificates, other identification and land deeds) awaited us with welcoming smiles. In the middle of the property were stakes laid out to mark the place where the new district center would be located (partially funded by Sarvodaya USA). On each side of the construction site were buildings that were being rehabilitated from tsunami damage. In the rear were debris and a tent filled with salvaged preschool supplies. Nelson took us into an office in the building behind the preschool (which had a newly painted mural of children on the side), where we sat down to a tropical fruit drink to look at pictures of the post-tsunami district center. The room where we sat was filled with water to the ceiling and all computers and supplies had been destroyed. In limited English, Nelson tried to explain to us how he’d been swept away by the wave but managed to survive by hanging onto the roof and door frame, how the preschool children were not inside the preschool that morning at 8:00 because it was a holiday, that 5 districts were affected, and that 27 of the impacted villages were within the Matara District. He then escorted us to the Pearl Cliff Hotel, where we were staying, in what has to be the highest piece of land in the area, and which undoubtedly is tsunami-proof.

Village Reconnaissance

The next morning we met with Nelson and our translator, Mr. Senerath, a retired government official, who led us through villages along the shoreline in the Matara District that had been severely damaged by the tsunami. We visited with the Shramadana Society Members in each village, who recounted the number of dead, wounded and the impacted structures and businesses in their village. Intermittently during our visits, Nelson relayed to us the dry rations, tents, medicines and books that Sarvodaya had distributed, and future plans to construct latrines and houses, and to provide counseling for women and children.

Kottagoda Village

The first person that we met was Samadhi Maheshica, the Society President of Kottagoda. She told us that out of 400 families in the village, 34 people had died (3 or 4 children, and the rest elderly) and 255 families had been affected. Sixty-two houses were fully and 192 houses were partially damaged. Most of the fisherfolk (the word they used to describe the fishing community) lost their boats and fishing supplies. The government granted the affected families 5,000 Rupees a month (or approximately $50) for two months, and a one-time allocation of 2,500 Rupees (or approximately $25) for kitchen utensils. Rations of 375 Rupees (or $3.75) a week per person were apparently still being distributed by a foreign agency, with about a third consisting of food stuffs (cheese, milk) and the remainder being distributed in currency.

Samadhi said that most of the people now had semi-permanent structures, yet, they were uncertain about when or whether they would get permanent houses because their destroyed homes were within the 100 meter zone from the coast that the government had declared could not be used for dwellings. Thus, they were in limbo,  stuck in either temporary structures or living with relatives, waiting for other lands to be located by the government on which they could build, if they only had the money to do so….

stuck in either temporary structures or living with relatives, waiting for other lands to be located by the government on which they could build, if they only had the money to do so….

We were told that many villagers escaped with only “what was on their backs.” They did not have medical supplies or physicians. People from several outside villages located in-land came to help with the clean-up in Shramadana or Sarvodaya work-camp efforts. The society president suddenly pointed out a young man that had appeared in front of us, who, he recounted, had lost a 2 month old child to “the wave.” He stood with his other child, of maybe two years, that they found stuck in the “V” of a tree root. Instinctively, I looked to see if the child appeared traumatized. Unfortunately he wouldn’t come near me, (all Sri Lankan children are traumatized by me—without exception they cry) so I couldn’t tell.

The town’s preschool had been damaged, and was outside the 100 meter zone. The preschool teacher, Gnaanawathie, said that she continued to teach even without a preschool although many of the children had left to go to schools in other areas. We wondered how they knew who would continue to be located in the village, what would be the structure of their Society (as a number of officers appeared to have lost their houses) and what children would come back to the preschool with the land situation as it stood.

Our translator said that the government had appointed a special officer for the disbursement of lands, and had changed the onerous land laws so that property transfers could be facilitated more quickly, but he added, “That takes time.” We encountered a “strike” against the government that closed Galle Road, which indicated to us that displaced people thought that time had run out.

Sudawella Village

In the village of Sudawella we were taken to meet the Secretary of the Shramadana Society, Vimla Abesuria. She recounted how Holcim Cement Company had donated cement, and in partnership with Sarvodaya, was constructing houses, which lowered the cost of building due to cement shortages (construction costs have gone up at least 2 times and of course there are stories of gouging). Society members and Nelson took us to a hilltop “neighborhood” where Sarvodaya was building houses for those who had the funds to purchase land there, which was a part of a larger project to build 42 houses in Matara (for which the Matara District has funding for 24). Notice that I said that the people who were building these donated buildings were people who had the money to buy property. Many villagers do not have such funds and are therefore left waiting for the government to act and allot land. So, the neediest suffer most.

The people that were “given” these houses were chosen by the Sarvodaya Shramadana Society in the village, based on criteria such as character, need, ability to purchase land and willingness to contribute to the construction process. Additional features such as red brick or more square footage had to be subsidized by the recipient. Apparently, there had been a lot of controversy and clucking about the people that were chosen. Therefore, the decision of the Society was carefully made, and was reviewed and approved by the District Coordinator. The houses that dotted the hillside—each at different stages of development—were designed by an architect for Sarvodaya. They were 500 square feet in size, were generally made out of cement blocks, had wood window trim and clay tile roofs, and seemed to fit organically within the area’s geography. Each home varied just enough in design, some with multiple roof lines or varied window frames. They appeared to be built so that there would be running water, several bedrooms, and a room with a place for a cooking fire.

We went back to the Society president’s house, which had been partially destroyed along with 20 other homes (30 totally destroyed). A cadre of family and friends gathered around us to tell us that most of the villagers (280 out of 390) lived within the 100 meter zone, and were therefore unsure about where to go or how to proceed. The Society president made it clear that she no longer wanted to live close to the water, a sentiment she said was shared by nearly all of the people in her village. You would never have known that these people lost so much, as we laughed and they recounted their stories. “What to do?” she asked (fortunately, a rhetorical question in Sri Lanka).

Five boats were partially damaged and had been repaired, and another 7 large boats were fully damaged. Rather than focus on the boat situation, people were dismayed about the fishing net situation! Most of their fishing nets had been washed away. They therefore couldn’t fish for income (instead they were living on the WHO ration of 375 Rupees a month) nor could they provide their families with food—fish was a main staple of their diet. Each boat employed 6 people, thus not only were they unable to provide for themselves, they were unable to provide for their 6 additional families. We quickly ascertained that there were 30 boats in that village, and that each boat needed at a minimum 10 nets a boat (roughly ½ the usual number), 5 or so small nets at 6,000 Rupees each, and 5 or so large nets for 7,000 Rupees each. Thus, outfitting each boat in that town with the minimum of nets would be 65,000 Rupees (or about $650), which times 30 boats equaled close to $20,000 US.

Gandara Village

In the village of Gandara we met Gunawaite, the Sarvodaya Village Bank Manager, who proudly showed us her wall chart of their bank’s progress since it opened in 1999.  They currently had 1071 members, 11,000,000 Rupees in savings, offered loans of 1 Lak maximum (100,000 Rupees), offered 15% interest on savings, and charged 20% interest on loans. So far so good I thought, until we were told that during the month of December Gunawaite had given 3, 1 Lak business loans to people who lost their homes and fishing boats in the tsunami. Obviously, they can’t make payments. She said that these people come to the bank from time to time and say, “some day we will pay you back.” The benefit of a village bank is that people are given loans at least partially based on their character, so she knows that they are good people, but good people in an impossible situation. A grace period of three months was granted, but now, people had to pay the interest on their loans monthly. She said that she would still give them business loans so that they could rebuild their businesses, but I wondered how many people would be willing to take on a loan when they couldn’t pay back the somewhat large one they already had. We sweated profusely as we all laughed, while we tried to jump start their ceiling fan, ate dohdol (a sweet desert of coconut oil, treacle and wheat flower) and sweet, fat, short bananas, tasted their sambol of Maldives Fish (that I mispronounced “moldy fish”—which garnered more laughter) and drank hot tea with milk.

They currently had 1071 members, 11,000,000 Rupees in savings, offered loans of 1 Lak maximum (100,000 Rupees), offered 15% interest on savings, and charged 20% interest on loans. So far so good I thought, until we were told that during the month of December Gunawaite had given 3, 1 Lak business loans to people who lost their homes and fishing boats in the tsunami. Obviously, they can’t make payments. She said that these people come to the bank from time to time and say, “some day we will pay you back.” The benefit of a village bank is that people are given loans at least partially based on their character, so she knows that they are good people, but good people in an impossible situation. A grace period of three months was granted, but now, people had to pay the interest on their loans monthly. She said that she would still give them business loans so that they could rebuild their businesses, but I wondered how many people would be willing to take on a loan when they couldn’t pay back the somewhat large one they already had. We sweated profusely as we all laughed, while we tried to jump start their ceiling fan, ate dohdol (a sweet desert of coconut oil, treacle and wheat flower) and sweet, fat, short bananas, tasted their sambol of Maldives Fish (that I mispronounced “moldy fish”—which garnered more laughter) and drank hot tea with milk.

Kiralavella Village

In the village of Kiralavella we were met by the bank manager, Djap Nandaweithie and the Society President, Nanda Sudasinghe.  The mood in the village was grim. As we stood just inside the village bank, one by one, villagers appeared and surrounded us. Several fishermen looked vacantly in our direction. None smiled. Their Society had been relatively developed: they had conducted Shramadana camps, nutrition programs, health clinics, Lamaze courses, children’s programs, and had a bank that had been in operation since 1990 with 629 members. The tsunami virtually wiped out their village. All but 3 families lived within the 100 meter zone. One hundred and ninety families (190) were affected by the tsunami, all of them fisher folk. Five houses had been fully and 42 houses had been partially damaged; twenty five people had lost all of their household goods. All told, 35 large and small boats had been destroyed. Engines were smashed—they had repaired 14, and dismantled another 5 for repair. Again, no one had nets and therefore there was no way for families to earn a living. Coir pits (a secondary income source from which mostly women make brooms and rope to sell) dug close to the shoreline were covered with rocks and soil and were therefore unusable. Divers lost their gems. Pit toilets destroyed by sea water, were dirty and unusable.

The mood in the village was grim. As we stood just inside the village bank, one by one, villagers appeared and surrounded us. Several fishermen looked vacantly in our direction. None smiled. Their Society had been relatively developed: they had conducted Shramadana camps, nutrition programs, health clinics, Lamaze courses, children’s programs, and had a bank that had been in operation since 1990 with 629 members. The tsunami virtually wiped out their village. All but 3 families lived within the 100 meter zone. One hundred and ninety families (190) were affected by the tsunami, all of them fisher folk. Five houses had been fully and 42 houses had been partially damaged; twenty five people had lost all of their household goods. All told, 35 large and small boats had been destroyed. Engines were smashed—they had repaired 14, and dismantled another 5 for repair. Again, no one had nets and therefore there was no way for families to earn a living. Coir pits (a secondary income source from which mostly women make brooms and rope to sell) dug close to the shoreline were covered with rocks and soil and were therefore unusable. Divers lost their gems. Pit toilets destroyed by sea water, were dirty and unusable.

Kapparatota North and South, Divisions of Weligama District

The Society members in the villages of Kapparatota North and South recounted that a full 58 houses had been partially or fully destroyed, 15 within the 100 meter zone, out of 997 families directly or indirectly affected. Although the story in this village seemed so much better than in others, dissension amongst villagers was slowing the structural and emotional recovery process. Some people within the 100 meter zone wanted to stay and rebuild, and some wanted to leave. “What would the government do to those who wanted to stay?” someone asked. “How could the government take people from their land?” someone else retorted. “I don’t think they will do it,” another person commented. The preschool had been fully damaged but another organization was reconstructing it.

Talalla South—A Village Ready for a Preschool

We arrived at Talalla South and were greeted by the Society Secretary, S.D. Punyawaithe, the Treasurer, Adjanta Edinsinghe and the Bank Manager, M.D. Paduma. In the background we could hear Buddhist chanting. This was a very large village of 1,056 families, and a total population of 5,820. Seventy three families were affected by the  tsunami, 284 had lost their jobs, 55 homes were fully and partially damaged, and 11 people died. Forty boats needed nets, 50 toilets needed constructing (families were sharing toilets), water was contaminated and wells needed to be built. The majority of men were fisherfolk, and women were coir workers. A considerable number had homes inside the 100 meter zone (350) and all agreed that they wanted to relocate inland, that they wanted to remain together as a village, and they had a plan to do so. Collectively, the displaced landowners had asked the government for apartments rather than houses: Less land would be required on which to place the construction, and well-built apartments were high off the ground and therefore out of reach of the water if such an event were to happen again, away from the beach anyway.

tsunami, 284 had lost their jobs, 55 homes were fully and partially damaged, and 11 people died. Forty boats needed nets, 50 toilets needed constructing (families were sharing toilets), water was contaminated and wells needed to be built. The majority of men were fisherfolk, and women were coir workers. A considerable number had homes inside the 100 meter zone (350) and all agreed that they wanted to relocate inland, that they wanted to remain together as a village, and they had a plan to do so. Collectively, the displaced landowners had asked the government for apartments rather than houses: Less land would be required on which to place the construction, and well-built apartments were high off the ground and therefore out of reach of the water if such an event were to happen again, away from the beach anyway.

It was at that moment that we looked at each other and realized we had finally found a village “ready” for a preschool, if indeed they needed one.

They did not have a Sarvodaya preschool, although a Buddhist Monk had given them a piece of land that would house the 50 or so children that would attend. We immediately headed over to the monk’s compound,  met him (Rathmalkekitiye Sirinanda) and saw where the preschool would be constructed (over where an existing well stood) and where the playground would be located (surrounding a Bodhi tree). It was the perfect match. We were poised to give money and support for building a preschool, and in Talalla South we had a village that we knew would stay together, that needed a preschool and that already had the foundation practically laid for one. We were exhausted, hot and sweaty and ready to rest.

met him (Rathmalkekitiye Sirinanda) and saw where the preschool would be constructed (over where an existing well stood) and where the playground would be located (surrounding a Bodhi tree). It was the perfect match. We were poised to give money and support for building a preschool, and in Talalla South we had a village that we knew would stay together, that needed a preschool and that already had the foundation practically laid for one. We were exhausted, hot and sweaty and ready to rest.

Lessons Learned

We learned some important lessons on this trip: A “permanent

building” such as a preschool may have to be followed by or built along with meeting other needs. If we had not been sent by our donors to specifically build a preschool, there were other items that screamed to us to be addressed also, particularly in the villages that were the most severely impacted. Counseling programs for tsunami-impacted villages, families and children need to be, and in fact are being initiated by Sarvodaya, alongside bricks and mortar projects. Toilets, wells and coir pits that were contaminated by sea water and debris, need to be reconstructed, built or cleaned. Land, private or governmental, requires locating or purchasing. Houses need constructing. Boats demand to be repaired and nets to be purchased.

Great post on a lovely project!

ReplyDeleteThanks. Hopefully, we'll be able to return in the fall, war permitting.

ReplyDeletevery interesting keep posting. Louisiana Secretary of State Corporations Search

ReplyDelete