Before we leave we lay down the law with the 18 year old son -- no having parties, no going to parties, no parties without booze, no parties with just a 'few friends,' no parties, period, no leaving the house, no going to N.O. and no heading off to Red River, NM skiing; and by the way "have fun." We kiss Grammy goodbye and head out the door. I thank God that Grammy is in good health so that we can leave home for a couple of days.

We are broke, but hurray, we double check: We have our credit cards.

Just before we get out the door, one of Daniel's future family members calls and wants to have dinner with us when we get into Metairie. I'm caught off guard. I manage not to answer -- as the last thing we want to do is talk to anyone tonight. I tell him we'll call him when we are on the road. I try to think of a reasonable reason to beg off, but really haven't come up with something "polite" to say before I nod off to sleep.

Then my phone rings just minutes after we get on the Interstate, and he wants to make plans. Now I'm starting to feel a little edgy. I tell him we are going to spend the evening and the next morning ALONE. I am tired. I do not tell him about the big fat drama week at work and at home, or that we need a break. I heave a bigger sigh than intended. I'm sure he hears it. He hangs up. I think I've probably been rude but am just too tired to reverse course.

I mention to Rich how glad I am that Deb didn't spend the money to come to our crazy house in the midst of so much craziness to watch such an obviously crazy parade in a crazy city, in a crazy state.

We arrive at the 1896 O'Malley House -- and let out another sigh, this time of relief. Rich parks his truck and we look out at a crowd of people already cordoning off their spaces on the island in the middle of Canal Street, where the Endymion parade will pass, which is exactly 1 1/2 blocks from where we are staying. It is 5:00 p.m. and the parade starts tomorrow at 4:15 p.m. We comment that it looks like a giant tailgate party, with food, drinks and a weird conglomeration of ladders and scaffolding being erected so as to view the parade better. I wonder, 'better than what?' as these folks will be on the front line of the parade route.

We meet Larry, the owner of the B&B, who shows us to our very nice cedar walled room with antique-ish furniture on the 3rd floor. He gives us our keys and reminds us to lock the front door every time we come in so that the folks outside "don't come in and pee pee on the floor." We go back down to our car, take out our suitcases, lock the door, and schlep our stuff up to the room.

Rich thinks he pulled his back out. He takes some pain meds, and admits to me that he is not sleeping well lately because our 18 year old son is leaving home for college soon. I wonder why he wouldn't be thrilled in anticipation of this send-off, but murmur something that sounds like I'm in agreement.

Eldest son, Daniel calls twice on the road, where he is in a traffic jam due to a multiple car wreck with fatalities, trying to make it to his future in-law's house in Metairie, near N.O. He tells us that future father-in-law is already staking out their spot on the parade route with various other family members "spelling" him out so that he can go home and sleep. We wonder why anyone would go to so much trouble just to watch a parade.

We hope we don't have to "spell out" anyone. We are dead-tired and may not wake up for the parade, let alone in the middle of the night for a walk to the beginning of the parade route to "spell out" people who feel that a parade is worth losing sleep over.

Besides, we are afraid of N.O. in the middle of the night.

We need to eat, so we walk four blocks and the first restaurant we see is Mandinas -- a little hole in the wall Italian restaurant on every restaurant guide in in the city, with a police patrol outside. There is a sign on the door that says,

"No checks, No credit cards. Cash only. ATM on the premises."

I do not think I have seen this before, except maybe in a lesser developed country. I make a comment to Rich about how rife with fraud N.O. must be for them to enforce a rule like this at a place of business where they actually want customers. I start feeling uncomfortable about walking the streets at night. We open the door, and I see a tacky sign at the back of the restaurant that says, "ATM," so I walk back and up a few steps near where people are eating, and try not to bump into them while retrieving several hundred dollars from our checking account. I hand it to Rich.

It occurs to me why the police patrol is outside -- to keep the bad guys away from the front of the restaurant.

To hell with you patrons as you head down the block or around the corner. We want your cash.

The last time I saw a police presence like this was in another country. Wait a minute: I have seen this in Baton Rouge, outside the Honey Baked Ham store at Christmas. At least there, we can park our car directly in front of the store and near the police.

We walk back to the waiting area, where a young Italian man with an earring shows us to our table, which is near the door and unfortunately behind a post, even though there are much better-placed tables that are free. I look at my clothes, and think to myself, "you're not dressed like a bum." I ask Rich if he thinks the young Italian man is a "Mandina" and he says, "No, he's not family." What criterion he's using to make that determination, I don't know. I'm feeling very unimportant but the waiter smiles at us, and I pretend he's a Mandina, just so that I don't feel like a second class citizen.

The restaurant is a classic. It has a huge cedar, glass backed bar, cedar wainscoting and sturdy Italianate furniture that looks like something grandma would have, where a view of the clientele and the owners are enough for the price of the meal.

We order their Friday special:

Eggplant, ham, shrimp and brown gravy with spaghetti meal

Almost immediately after receiving it I feel terrible eating all of these calories, so I selectively eat bites out of the gravy plate and most of the spaghetti, which seemed like the lesser of the two evils.

It is all delicious.

I look around. I'm pretty sure that most of the waitstaff and customers have been there since 1932, the year of their opening: two towering gentlemen in white waiter's gear and ties, probably at least 300 lbs, and in their 70s, distinguishable because one has a goiter and the other does not; a woman in the corner that looks like an obese 80 year old Marilyn Monroe; some handsome couples in jogging gear with their beautiful children in front of the bar; some young Italian men; quite a few established New Yorkish looking families; and a burn victim and his wife. For some reason the restaurant looks like it is filled with characters from a movie. I keep telling Rich to "look" at various people behind him; he is facing the door as usual. Each time he says, "no," I point loudly to one of the cheap paintings on the rear wall so he'll have a reason to turn around and stare.

I order Cabernet. They say they have Merlot. I say, OK. It tastes like Sherry, and although I hate Sherry it fits the mood of the place.

I text James twice telling him that although he's 'in trouble' I love him. I'm beginning to miss him and feel sad that he is leaving the house for college in 6 months. I look at my watch: That change of heart took approximately 3 hours.

The next morning I roust Rich and we head on down to breakfast. I am craving coffee and drink maybe 5 cups, and of course eat breakfast, which I never do, because "it's there" and I'm "on vacation" and "it's Mardi Gras." The breakfast consists of fruit (good for me), yogurt (good) coffee (okay) with cream (not good) and an Italian Quiche made with filo dough (not good) and sausage (definitely not good).

It is all delicious.

I refuse the homemade biscuits, which makes me feel somewhat disciplined.

Larry tells us that Mandinas was a purported mafia hangout for years, and it dawns on me that the cash-only policy has more to do with money laundering than it does with fraud, which makes me feel a lot more comfortable about walking the streets with money and a credit card jammed in my front pockets.

No bare faces on floats: It is against the law to take off your mask and the mesh face-cover underneath

No bare faces on floats: It is against the law to take off your mask and the mesh face-cover underneath The future grandfather-in-law calls and wants to know where we are because the future-grandmother is going to drop off a Mardi Gras bag she made, complete with beads to get me started. He wants us to check out tomorrow morning at 8:30 to follow him to a parking lot close to the bleachers were they've paid for our tickets to watch 4 parades from 12:00 p.m. tomorrow to 12:00 a.m. tomorrow night.

I panic. I cannot sit still for 12 hours and watch 4 parades. I beg Rich to ask them where the bleachers are -- we'll try to catch a cab or the trolley across town and just leave from our B&B at a more civilized hour. They say it's "miles and miles" away and "the street cars don't operate when there are parades."

They then suggest that we not watch the parade today with Daniel's future in-laws (their son and daughter-in-law). They say, "just go outside your door and watch from your Bed and Breakfast;" "You'll never find Tommy and the family, there are thousands of people out there;" the location is "miles" from you; and finally, "Tommy is cranky." All the while, we hear Larry, the B&B proprietor yelling in the background, "You're maybe a mile at the most from them. I walk the dog there every day." Daniel calls twice, he gives Rich the parade location. We GPS it, and it's 8 blocks from here. I calm down. We can do that.

He calls again and tells Rich that Tommy and Alfie haven't rented a port-a-potty this year, but they have rigged up a "bathroom like structure" on the back of his truck (now I remember Brandi telling me that they have used it in the past for #1 but not #2). Okay. The port-a-potty concept was probably the only reason I agreed to be on the parade route and not watch these parades on television (are they on television?).

I take a shower and get ready for the big extravaganza. When I get back to our room, I notice that the future grandmother has dropped off my Mardi Gras bag. She has indeed decorated it with sparkly paint, it has big beads in it, and several moon pies. It is adorable. I vow to myself that I will not eat the moon pies.

Enough is enough. I struggle to put on my pants. Didn't they fit just yesterday?

Daniel calls twice more. He wants us there now. Rich is asleep. I wake him up and tell him that we really need to get started walking to our spot on the parade route, it's after noon and our tribe has been there since yesterday morning at 5:30 a.m. He wakes up, gets dressed and off we go, but not before he tells me he's disappointed in me for spending time on the computer this morning instead of spending time with him. "Oh Shoot," I think. "He's right. I'm an idiot. I was just trying to recharge my batteries, which didn't include recharging him." Bad wife. I run along after him apologizing. He says it's okay, but it's not.

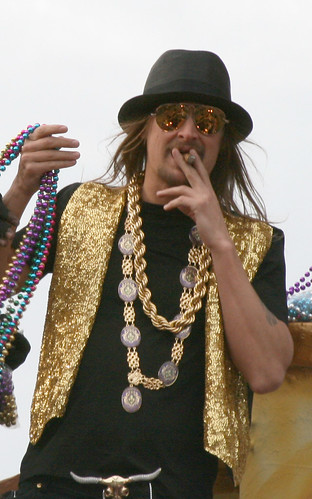

We finally arrive at the spot Daniel's future family members have staked out, which is just a block from the bandstand where Kid Rock, the Grand Marshall and REO Speedwagon will perform. I am genuinely happy to see the whole family. Familiar faces amongst thousands. Hugs and kisses all around. We're let into the gated area. I'm offered food from the feast they have prepared, and a beer, but I trade it in for an "Ice Pick." We are offered a place on the ladder, front-row seats and places to stand. More hospitality than we deserve, after all we haven't done anything to contribute.

Minutes turn into hours and I find that I'm smiling again. Rich says, "This has significantly exceeded my expectations."

We relax and celebrate for the next 8 hours. Thirty floats, probably 15 bands, maybe 8 sets of gas flambeaux carriers (traditionally African American men that originally carried paper-lit-lanterns in the early 17th century when there were no lights to illuminate the evening parades), a king, a queen and various princesses, all on custom designed floats, and probably 30 pounds of beads, all make the parade memorable.

What makes it exceptional is that thousands of people, young and old, large and small can be jammed into a fixed space, in an alcohol-fueled environment and get along so well. We feel like there is a possibility of a brother and sisterhood of men and women. We are happy, content and smiling. Maybe it's the Ice Picks, maybe the exhaustion, or maybe it's simply that we were welcomed and given a place to rest. For the moment, we love Louisiana. We have 'family here.'

Now, I wish Deb had spent her money to come to New Orleans to experience it with us.

For the record, the make-shift port-a-potty is genius. It's inside a Ford Van with plastic hefty bags taped to the windows. It's clean and was made by Daniel's future in-laws' grandfather when the girls (future mother-in-law and her sister) were little. Someone has to stand guard outside the van while someone is doing their business. Even the place where we put our little tushies has a historical familial connection. I like that.

After the parade ends, we pick our way through screaming crowds of people to make it back to our Bed and Breakfast, which happens to be along the parade route. This means that we are backtracking along Carrollton, and catch-up to the parade that we had just finished seeing as it careens to the Convention Center. We walk with the floats all the way back to Canal Street. I feel like we are "in" the parade. Rich and I take hundreds of pictures of the absolute insanity. By that time the barricades have been torn down, people are pressed up against the floats in a frenzy of bead throwing and catching. We are trying to walk the very narrow space in between the floats and the clamoring crowds.

A very tall black woman raises up her baby to kiss a masked man in a purple, fuzzy hat. The baby kicks me in the head. She is aghast and very apologetic. I keep telling her it is okay; that it did not hurt. He's just a baby, with baby feet. But, she puts her large arms around me and gives me a big hug, then kisses the top of my little pin head. I grin. This will be forever the metaphor for me that is Mardi Gras.

The next day before we leave, we have breakfast with a number of other Mardi Gras visitors, and Larry who owns the B&B. Most of the visitors have a strong connection to Louisiana, either having lived here or visited here for years. We learn that each of the floats are made up of people that pay to be on them (from $400 to $2000). These fees apparently take care of the money for the police escorts, the marching bands, and the floats. They also pay for all of their own beads, their costumes, and the food they eat at their respective Balls. Now I am even more thankful for the beads that these men, mostly, have thrown to me, because they have paid for them out of their own pockets. Larry calls it the least expensive, best entertainment in the world, and I think he is right.

The last mental picture I have is of Larry dressed in his big black afro, riding his vespa from party to party through Mardi Gras crowds on parade nights, with Cody, his Golden Retriever chasing after him.

We come back home to Baton Rouge to our real lives. We "lost" James last night (we couldn't locate him) which is why we came home early and did not go to an additional day of parades. My mother has two new physical symptoms that need a doctor's attention. Our house is a mess. And, just as we were pulling into the driveway, Grammy was trying to back out and ran into my car, which now needs body-work.

I pick-up our ailing cat "Gray" from the vets. I make dinner. I wash clothes, and hang up my jeans to dry (no dryer) so that I can fit in them for the next few weeks, or until I lose weight.

I'm feeling tired but remarkably rejuvenated.

We decide to do this all again next year. We will go 24 hours earlier so that we can help claim a great spot on the parade route, and "spell" out those family members that need it. We will help cook and mix drinks. We will buy a ladder or two for our grandchildren. We will go to 4 parades the next day with the grandparents-in-law. It will be a wonderful time. We can't wait!

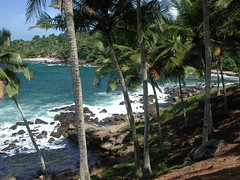

identified, to choose the most appropriate village in which to build. Traveling on the coastal road (Galle Road) the devastation was still apparent, the majority of which appeared to be around the City of Galle itself. Houses and other structures were totally ripped from their foundations, with partial cement walls standing to mark the place where the structures had been. In other instances, nothing was left except rubble or garbage strewn on the ground.

identified, to choose the most appropriate village in which to build. Traveling on the coastal road (Galle Road) the devastation was still apparent, the majority of which appeared to be around the City of Galle itself. Houses and other structures were totally ripped from their foundations, with partial cement walls standing to mark the place where the structures had been. In other instances, nothing was left except rubble or garbage strewn on the ground.

Individuals were busy mending walls of structures along the road with whatever materials they could find. Toward the District of Matara, however, the tsunami devastation appeared to be less severe, and that there was a greater organized repair effort underway. Mr. Senerath told and retold stories of Buddha statues, shrines and stupas that were untouched by the tsunami, some right next to great piles of wreckage, and about dogs that alerted their owners and retreated inland before the tsunami struck.

Individuals were busy mending walls of structures along the road with whatever materials they could find. Toward the District of Matara, however, the tsunami devastation appeared to be less severe, and that there was a greater organized repair effort underway. Mr. Senerath told and retold stories of Buddha statues, shrines and stupas that were untouched by the tsunami, some right next to great piles of wreckage, and about dogs that alerted their owners and retreated inland before the tsunami struck. stuck in either temporary structures or living with relatives, waiting for other lands to be located by the government on which they could build, if they only had the money to do so….

stuck in either temporary structures or living with relatives, waiting for other lands to be located by the government on which they could build, if they only had the money to do so…. They currently had 1071 members, 11,000,000 Rupees in savings, offered loans of 1 Lak maximum (100,000 Rupees), offered 15% interest on savings, and charged 20% interest on loans. So far so good I thought, until we were told that during the month of December Gunawaite had given 3, 1 Lak business loans to people who lost their homes and fishing boats in the tsunami. Obviously, they can’t make payments. She said that these people come to the bank from time to time and say, “some day we will pay you back.” The benefit of a village bank is that people are given loans at least partially based on their character, so she knows that they are good people, but good people in an impossible situation. A grace period of three months was granted, but now, people had to pay the interest on their loans monthly. She said that she would still give them business loans so that they could rebuild their businesses, but I wondered how many people would be willing to take on a loan when they couldn’t pay back the somewhat large one they already had. We sweated profusely as we all laughed, while we tried to jump start their ceiling fan, ate dohdol (a sweet desert of coconut oil, treacle and wheat flower) and sweet, fat, short bananas, tasted their sambol of Maldives Fish (that I mispronounced “moldy fish”—which garnered more laughter) and drank hot tea with milk.

They currently had 1071 members, 11,000,000 Rupees in savings, offered loans of 1 Lak maximum (100,000 Rupees), offered 15% interest on savings, and charged 20% interest on loans. So far so good I thought, until we were told that during the month of December Gunawaite had given 3, 1 Lak business loans to people who lost their homes and fishing boats in the tsunami. Obviously, they can’t make payments. She said that these people come to the bank from time to time and say, “some day we will pay you back.” The benefit of a village bank is that people are given loans at least partially based on their character, so she knows that they are good people, but good people in an impossible situation. A grace period of three months was granted, but now, people had to pay the interest on their loans monthly. She said that she would still give them business loans so that they could rebuild their businesses, but I wondered how many people would be willing to take on a loan when they couldn’t pay back the somewhat large one they already had. We sweated profusely as we all laughed, while we tried to jump start their ceiling fan, ate dohdol (a sweet desert of coconut oil, treacle and wheat flower) and sweet, fat, short bananas, tasted their sambol of Maldives Fish (that I mispronounced “moldy fish”—which garnered more laughter) and drank hot tea with milk.  The mood in the village was grim. As we stood just inside the village bank, one by one, villagers appeared and surrounded us. Several fishermen looked vacantly in our direction. None smiled. Their Society had been relatively developed: they had conducted Shramadana camps, nutrition programs, health clinics, Lamaze courses, children’s programs, and had a bank that had been in operation since 1990 with 629 members. The tsunami virtually wiped out their village. All but 3 families lived within the 100 meter zone. One hundred and ninety families (190) were affected by the tsunami, all of them fisher folk. Five houses had been fully and 42 houses had been partially damaged; twenty five people had lost all of their household goods. All told, 35 large and small boats had been destroyed. Engines were smashed—they had repaired 14, and dismantled another 5 for repair. Again, no one had nets and therefore there was no way for families to earn a living. Coir pits (a secondary income source from which mostly women make brooms and rope to sell) dug close to the shoreline were covered with rocks and soil and were therefore unusable. Divers lost their gems. Pit toilets destroyed by sea water, were dirty and unusable.

The mood in the village was grim. As we stood just inside the village bank, one by one, villagers appeared and surrounded us. Several fishermen looked vacantly in our direction. None smiled. Their Society had been relatively developed: they had conducted Shramadana camps, nutrition programs, health clinics, Lamaze courses, children’s programs, and had a bank that had been in operation since 1990 with 629 members. The tsunami virtually wiped out their village. All but 3 families lived within the 100 meter zone. One hundred and ninety families (190) were affected by the tsunami, all of them fisher folk. Five houses had been fully and 42 houses had been partially damaged; twenty five people had lost all of their household goods. All told, 35 large and small boats had been destroyed. Engines were smashed—they had repaired 14, and dismantled another 5 for repair. Again, no one had nets and therefore there was no way for families to earn a living. Coir pits (a secondary income source from which mostly women make brooms and rope to sell) dug close to the shoreline were covered with rocks and soil and were therefore unusable. Divers lost their gems. Pit toilets destroyed by sea water, were dirty and unusable. tsunami, 284 had lost their jobs, 55 homes were fully and partially damaged, and 11 people died. Forty boats needed nets, 50 toilets needed constructing (families were sharing toilets), water was contaminated and wells needed to be built. The majority of men were fisherfolk, and women were coir workers. A considerable number had homes inside the 100 meter zone (350) and all agreed that they wanted to relocate inland, that they wanted to remain together as a village, and they had a plan to do so. Collectively, the displaced landowners had asked the government for apartments rather than houses: Less land would be required on which to place the construction, and well-built apartments were high off the ground and therefore out of reach of the water if such an event were to happen again, away from the beach anyway.

tsunami, 284 had lost their jobs, 55 homes were fully and partially damaged, and 11 people died. Forty boats needed nets, 50 toilets needed constructing (families were sharing toilets), water was contaminated and wells needed to be built. The majority of men were fisherfolk, and women were coir workers. A considerable number had homes inside the 100 meter zone (350) and all agreed that they wanted to relocate inland, that they wanted to remain together as a village, and they had a plan to do so. Collectively, the displaced landowners had asked the government for apartments rather than houses: Less land would be required on which to place the construction, and well-built apartments were high off the ground and therefore out of reach of the water if such an event were to happen again, away from the beach anyway.

met him (Rathmalkekitiye Sirinanda) and saw where the preschool would be constructed (over where an existing well stood) and where the playground would be located (surrounding a Bodhi tree). It was the perfect match. We were poised to give money and support for building a preschool, and in Talalla South we had a village that we knew would stay together, that needed a preschool and that already had the foundation practically laid for one. We were exhausted, hot and sweaty and ready to rest.

met him (Rathmalkekitiye Sirinanda) and saw where the preschool would be constructed (over where an existing well stood) and where the playground would be located (surrounding a Bodhi tree). It was the perfect match. We were poised to give money and support for building a preschool, and in Talalla South we had a village that we knew would stay together, that needed a preschool and that already had the foundation practically laid for one. We were exhausted, hot and sweaty and ready to rest.